Photos

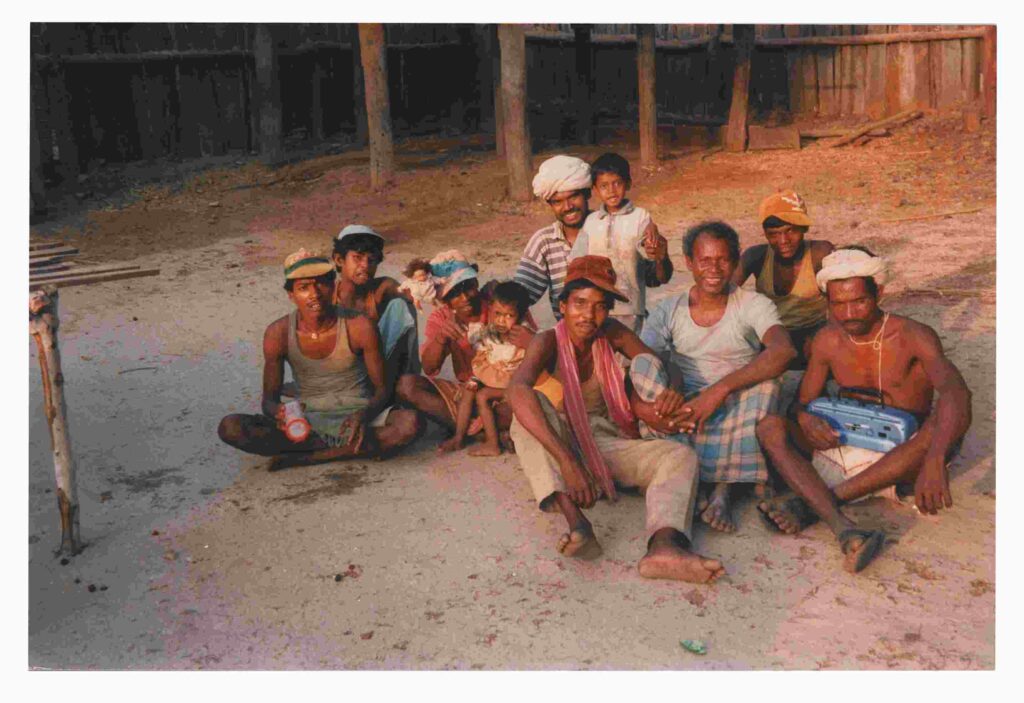

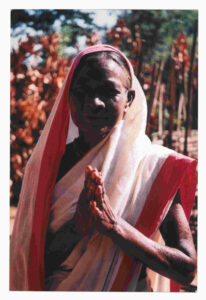

The following pictures were taken during my PhD fieldwork in years 1998-1999 in the Porahat area of West Singhbhum, Jharkhand. I took pictures only rarely and towards the end of my fieldwork. In those years, digital cameras (let alone mobile phones!) were hardly available while “normal” cameras required films and batteries that were quite expensive for a student like me. Ultimately, photography was not my focus and I took pictures only rarely. Now of course I regret not having captured so many interesting aspects of daily life in those two villages. Whatever picture I managed to take, I am now sharing it with you.

Few things to keep in mind:

1. The photos on this website are freely available in low-definition versions.

2. If you require an HD version, please contact me with the file number using the message section.

3. An acknowledgement of Dr Barbara Verardo and AdivasiFieldNotes is required for any non-commercial use of photos,

including exhibition, academic research and education purposes.

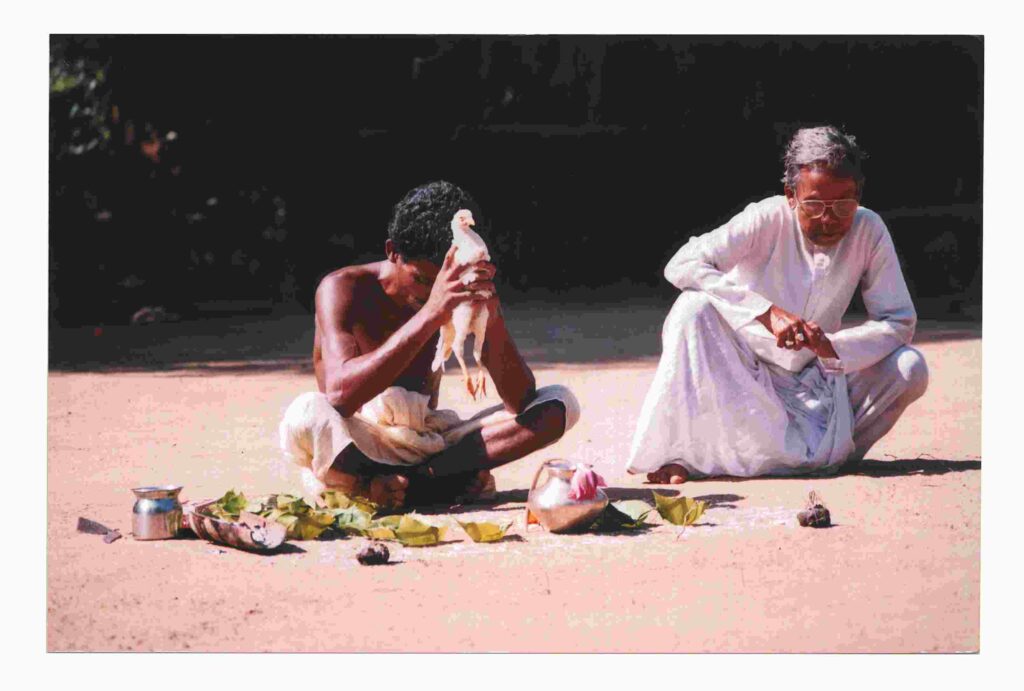

Ancestral Practices

Local ancestral practices are generally defined as bongaburu (spirits of the forest) or ‘rules that root’ (red: dharom): by worshipping the local spirits, people ‘root’ into the territory. They lack any anthropomorphic reference (except Singbonga, also defined as ‘the old man’ yet perceived as being everywhere and seeing everything) and are instead associated with natural sites: water, hills, upland, and low-land rice fields, the sun, the moon, the forest, and so on. They are all carnivorous. With the exception of najom bonga and churin bonga, all other spirits have a positive connotation (bugin bongako). Village spirits (Singbonga, Nage-era, and Deshauli bonga) are associated with a particular sacrificial animal (a white fowl, a black one, and a red fowl respectively).

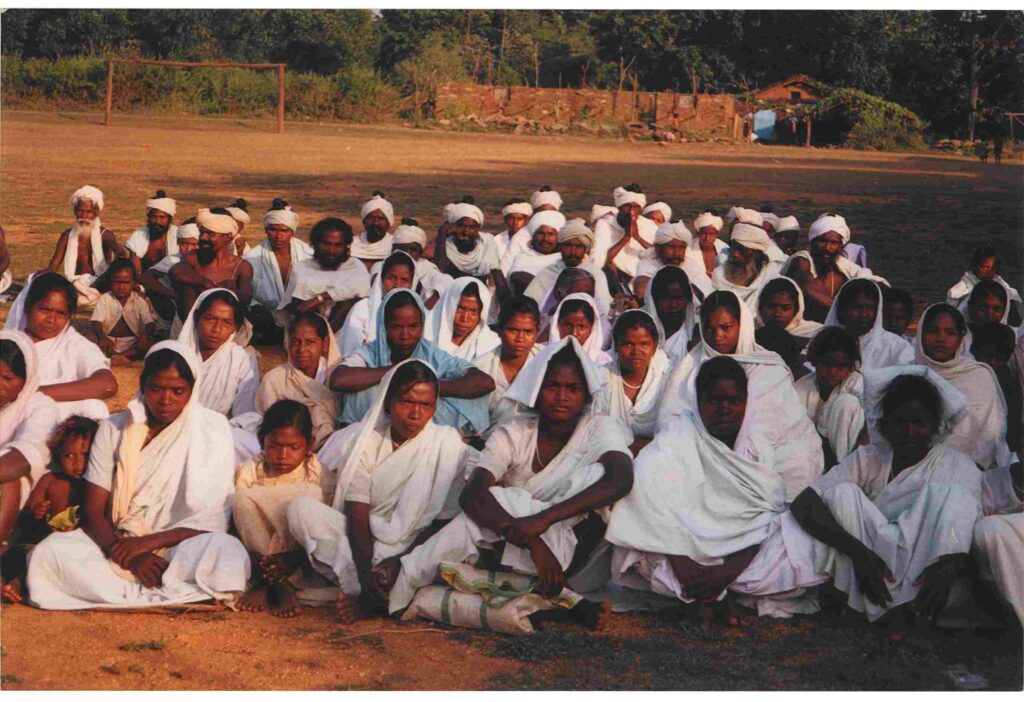

Birsa Munda dharom

Porahat area was the centre of one of the major adivasi revolts in Chotanagpur, the Birsa Munda Movement of 1895-1900. Initially a religious reformist movement tainted both with Vaishnava and Christian elements, it soon acquired a political dimension. Its leader, Birsa Munda, envisaged an apocalyptic ‘resurgence’ of what was then conceived as the ‘original’ Munda kingdom. The climax of the conflict was reached on Christmas Eve of the year 1900. After his death, the movement transformed into a messianic sect, the Birsa Dharom. The sect still survives today and is particularly active in the area under study.

Budh/Shiuli dharom

The Shiuli dharom is a very local Hindu reformist movement introduced by a pujari from Shiuli village in central Bihar in the 1920s – a period of religious crisis after the collapse of the Birsa Munda rebellion. Shiuli converts self-identified as Buddhists as they worship Gautam Buddha. Curiously, Shiuli is a Muslim village famous for its Sufi saint tomb and a site of pilgrimage!

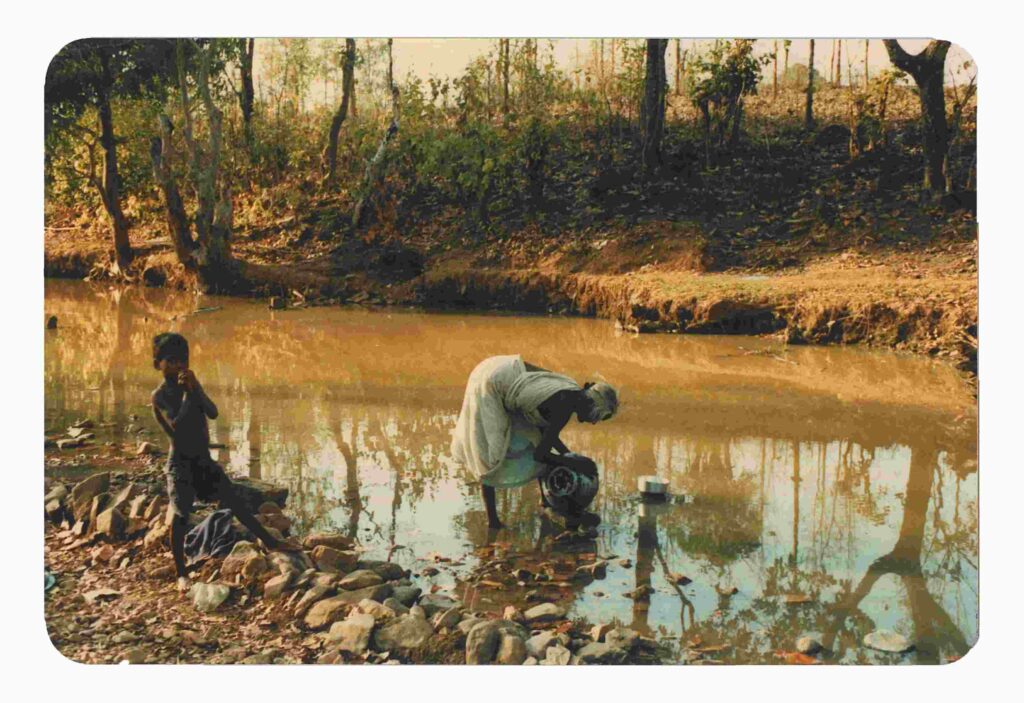

Daily Life

The pictures below give a glimpse of daily life and housework in remote, forested villages of Jharkhand: bathing and washing dishes by the river, collecting water, fixing the roof before the rainy season starts, coating the courtyard flood with cow dung and mud paste, making and fixing mats, and so on.

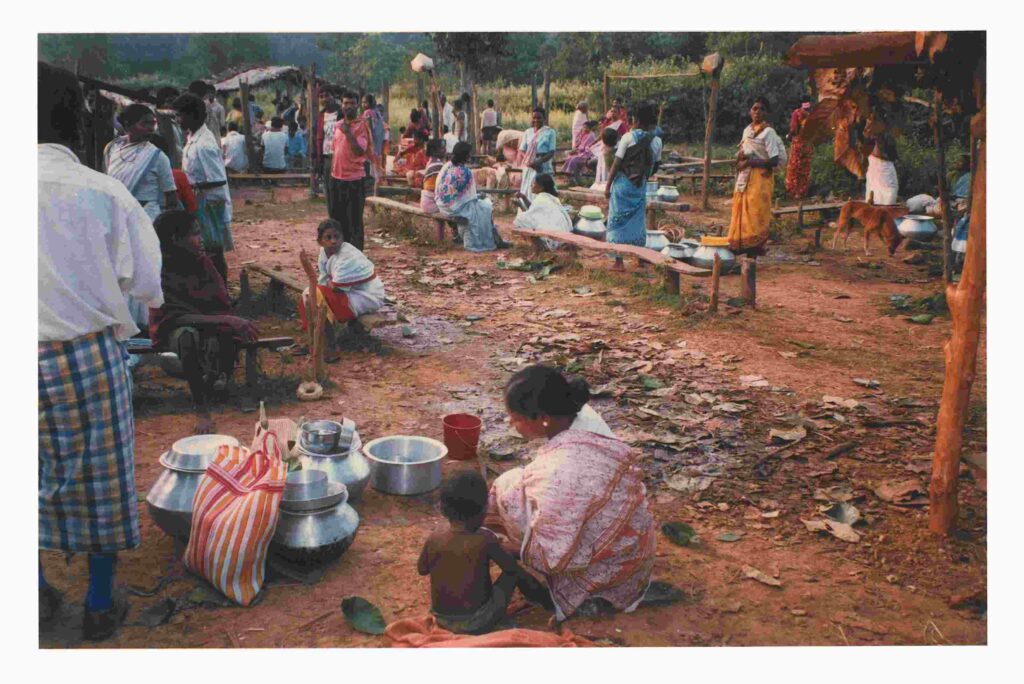

Economic activities

Land and forest constitute the main economic resources in the area under study: agriculture, collection and trade of forest produce, fishing, hunting, and so on.

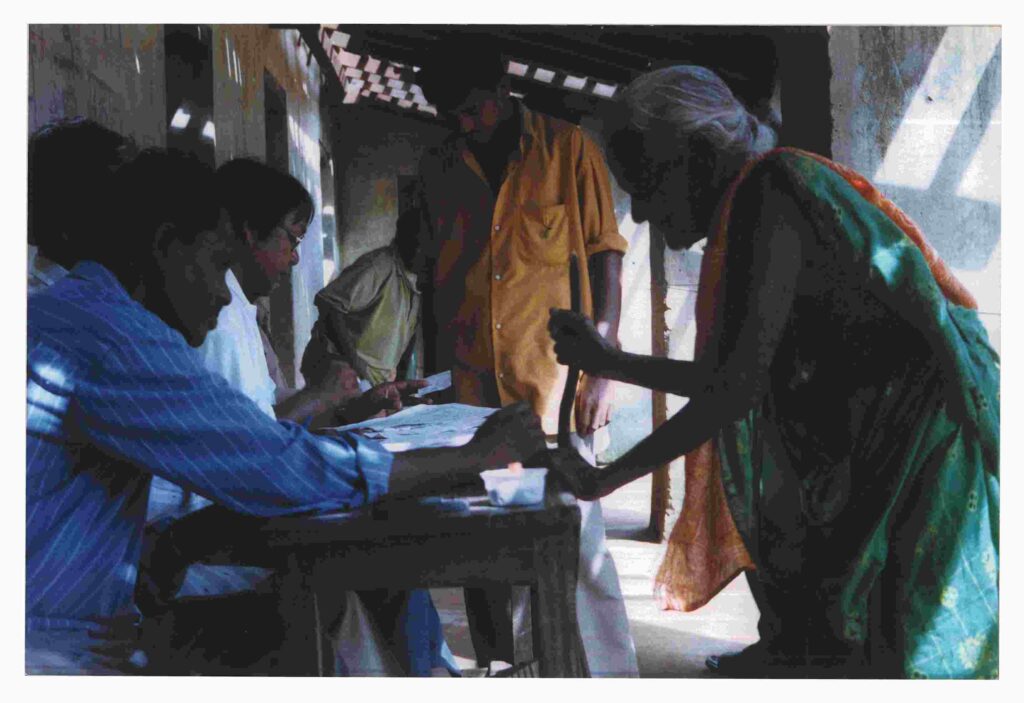

Political activities

Land and forest have also a political dimension as they are associated to the adivasi identity. The same word “Jharkhand” is also used as a verb to express pioneering activities. The areas under study was very active politically with many grassroots events.

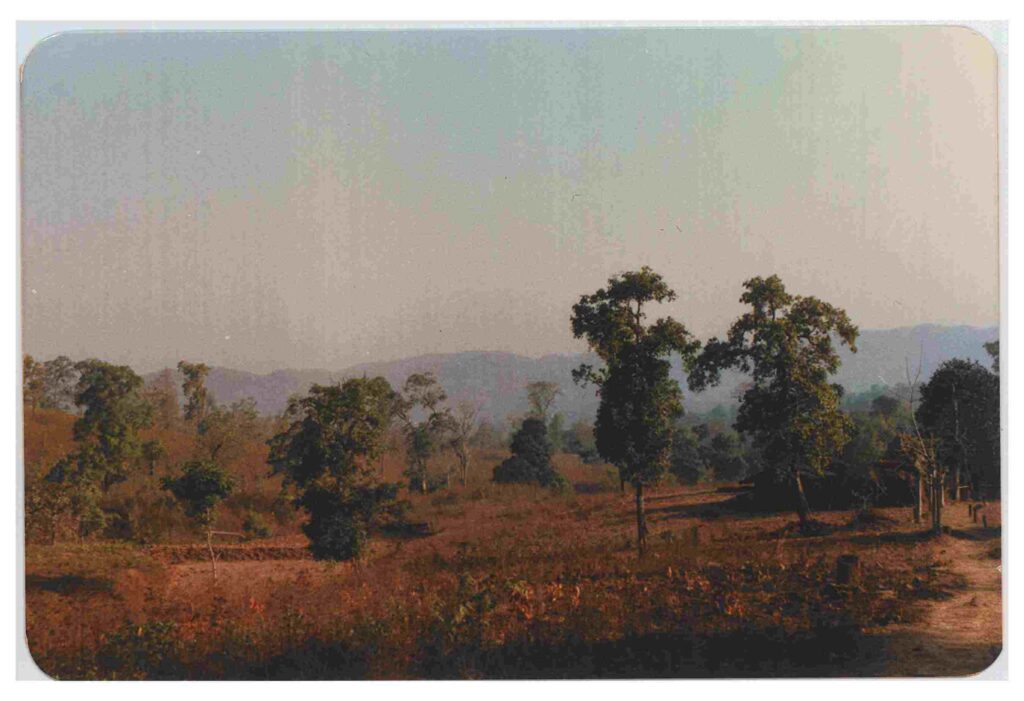

Landscape

Jharkhand means land of forest. The pictures below show the beautiful landscapes of the area where I conducted my fieldwork.